“evento da pompéia 2014.” Paulo Ito. Courtesy of the artist CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

News and social media around the world are carrying stories about the tear-gassed transportation strikers in São Paulo, violence and conflict with the police in Rio’s favelas, and – witty but no less serious – John Oliver’s scathing explanation of the problems with the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), which drew on major media reports about the organization’s well-known illegal cash-for-contracts corruption, and also its scandalously legal pillaging of World Cup host countries.

For those who have been following the preparations for the World Cup in international reporting, or this forum, strikes, protests and corruption are no surprise. Yet a major US news organization such as the New York Times has only one story, by the reliably attentive reporter Simon Romero, about Brazil on Edge as World Cup Exposes Rifts. The other thirty-odd pieces on their World Cup coverage page are largely fluff, ranging from the World Cup Hairdo Hall of Fame to the appearance of colored cleats. So it is understandable if readers relying on mainstream US news, or soccer fans focused on the teams and upcoming matches, are not well-informed about why the World Cup presents Brazil’s population with a host of internal conflicts and tensions, on the eve of the games.

the Cup provides a narrow window of increased bargaining power

The current “unrest” has been long planned. To pick up but one thread: the phrase “Não Vai Ter Copa” – roughly, “No World Cup!”– became a rallying cry in 2013’s June and July demonstrations, held around Brazil. Those protests, not quite as spontaneous as they seemed, had roots that went further back, to activist groups such as the Movimento Passe Livre or Free Fare Movement, that were organized in the World Social Forum on Porto Alegre in 2005, as well as older social movements such as the Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST), an off-shoot of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST). These nuclei of organization and the early protests they held were given momentum in that 2013 season by the diligent reporting by media activist groups, such as Media Ninja, who documented police aggression and brutality toward the protesters. Images and videos spread via social media until the mainstream media also picked up the story, catalyzing greater participation. In the more recent strikes, the “No World Cup” call has been affixed to many demands for things: better wages by the São Paulo transportation strikers, for example, for whom the Cup provides a narrow window of increased bargaining power.

Another factor in both last year’s events and the current protests is that there is in fact a mechanism for popular participation in government, by way of participatory forums that operate from the municipal to the national level. From their roots in local participatory budgeting projects, the groups offer ways for communities to decide matters pertaining to their own governance. Much earlier in the planning process, these committees held intense discussions about the World Cup, debating what should and should not happen: existing communities, even precarious ones, should not be displaced, for example. Their voices may have been heard, but were ignored.

Full report available at the Pew Research Center

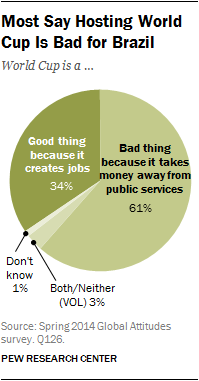

Thus, there is considerable apathy about the games in Brazil, as well as anger at how they’ve been organized. In a new Pew Center Research survey, helpfully titled “Brazilian Discontent Ahead of World Cup,” 61% (six in ten people) said “hosting the event is a bad thing for Brazil because it takes money away from schools, health care and other public services.”

One-sided enrichment for FIFA comes partially from the “not-for-profit” organization’s requirement that it be exempt from taxes, thus depriving governments at the municipal, state and federal levels from recovering financial investments in World Cup infrastructure projects. What citizens of the host country are left with are earnings from tourism, estimated to come in at 0.4 percent of GDP, or about $11.1 billion USD, and the projects themselves, including stadiums, and their subsequent upkeep. Brazil has built twelve stadiums, four in cities that are not expected to be able to sustain them afterward, as they do not have major soccer teams.

And corruption, notably, is not limited to FIFA: the AP news agency found that the companies that had won the most World Cup development projects had also massively increased their campaign contributions of late. In Brazil’s capital city, Brasília, one of those which has no major professional team, government auditors found that the cost of building the new Mané Garrincha stadium had tripled to $900 million USD in public funds due to allegedly fraudulent billing and money lost when fines were inexplicably not enforced for failing to complete parts of the project on time.

The World Cup preparations as a whole are reported to be around $15 billion USD…more than the Cups in South Africa 2010 and Germany 2006 combined.

There has been considerable debate in Brazil about how much this Cup has cost, and how much has been paid for with public money. In an excellent piece by the Agency of Reporting and Investigative Journalism, Publica, the authors report that despite the claim by the Minister of Sports, Orlando Silva, in 2007, that “There will not be one cent of public money for the World Cup stadiums,” at least $2.1 billion for building had come from public coffers. While their conservative number covers only documented loans, and funds confirmed by the host state governments (six of which did not respond), other estimates put the total of public funds somewhere between $3.6 and 4.3 billion USD. The World Cup preparations as a whole are reported to be around $15 billion USD, a number that seems to get revised up another billion daily, and which is more than the Cups in South Africa 2010 and Germany 2006 combined. That money has been invested almost entirely in the stadiums, leaving unfilled the promises of subways, highways and other infrastructure projects. Moreover, as researcher Christopher Gaffney explains, since at least seven of the stadiums constructed with public money are slated to be handed over to Public Private Partnerships, the state has effectively financed private companies to make a profit, while simultaneously privatizing public space.

As well, each project has come at human cost: activists have estimated that as many as 250,000 people have been displaced throughout the country in the Cup preparations, moved to distant parts of their cities, and inadequately compensated by the state for losing their homes. The Brazilian government has not hazarded a recent estimate, but in an earlier assessment counted 170,000 people who ran the risk of being forced from their homes. And, as described in other Anthropoliteia posts, communities have been subjected to “pacification” efforts that putatively aim to evict gangs and establish a regular police presence, with mixed results.

The TELERJ favela was founded by 5,000 people in a set of abandoned buildings a few miles from Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro, in March 2014. They were forcibly evicted by the government in April. Photo courtesy of Mídia NINJA CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Such injustices and the protests they have incited, together with corruption, overspending and an apparent lack of results, have contributed to a sense of malaise and suspicion. The researchers Ana Paula da Silva and Thaddeus Gregory Blanchette offer a series of anecdotal “bad omens for the World Cup,” including a conversation with a taxi driver who was certain that the Cup was ultimately rigged. He told them,

“It’ll be just like France in ’98 or Argentina in ’78. There will be a miraculous victory for Brazil. God himself will come down from on high and point His finger at our team. That is the only way they’ll be able to recover some enthusiasm for this whole sorry business. They’re planning it now. Just you wait and watch, boy.”

Caption: “The university is not FIFA’s. It’s the people’s. 2014. Photo by Grupo de Educação Popular UERJ

Little reported outside of Brazil itself have been the ways that basic “rights to the city” are integral to the protests, and are being limited during the World Cup. Together the examples create a rather undemocratic picture. The State University of Rio de Janeiro, (UERJ), near the stadium, has been rented by its dean to FIFA for parking and so that the TV network Globo can transmit the games, for an amount undisclosed to the rest of the academic community. Classes have been suspended until mid-July. The semester will be extended in August, and the following semester until January. Some view this as a way for the school to earn money and eventually renovate its facilities, but the receipt for the rental has not been produced. A $50 million dollar walkway over a busy and dangerous thoroughfare which has been built between Rio’s Maracanã stadium and the Quinta da Boa Vista, a large park with a zoo and museum in the otherwise unremittingly urbanized neighborhood of São Cristóvão, will be reserved for VIPs for the duration of the Cup, while the Quinta will be have space for sponsors.

Despite widespread dissatisfaction “with the way things are going in their country” (72% of the population, according to Pew), Brazilians are almost equally divided on whether protests are effective, and also on whether now is the right time, since there are those who feel that the protests and lack of spirit make look Brazil look bad abroad. The same survey asked whether last year’s protests had a positive or a negative effect, and found that “47% say the protests were a good thing for Brazil because they brought attention to important issues and 48% say they were bad because they damaged the country’s image around the world.”

The mood in the country is split, and this is already a huge change from previous Cups. Many have ridiculed the rallying cry of “No World Cup,” since the games will surely take place, even if this means brutal repression of protesters and the unsettling detention of activists by the police. But, as others have explained, already “there was no World Cup,” and “there will have been no World Cup.” There were of course always people who didn’t really care about the games, although the chances are they ended up watching anyway. But already there can be none of the unity – a collective agony and joy – that made watching the World Cup in Brazil, no matter where is was hosted, truly participatory.

Meg Stalcup (PhD, University of California, Berkeley and San Francisco) is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University to Ottawa and editor of selections concerning visual anthropology, visual ethnography, and visual criminology for Anthropoliteia.

Pingback: DragNet: June 1 – 15, 2014 | Anthropoliteia

Pingback: Around the Web Digest: Week of June 8 | Savage Minds

Pingback: The Other Side of the Bay Social Consequences Across from Rio de Janeiro | Anthropoliteia

Pingback: The Politics of Violence and Brazil’s World Cup | Anthropoliteia

Pingback: The Politics of Violence and Brazil’s World Cup (Anthropoliteia) | Uma (in)certa antropologia

Pingback: Todos morirán - Revista Anfibia

Nice blog youu have

LikeLike