Welcome back to In the Journals! This ongoing series aims to bridge conversations that are often siloed by discipline, geographical region, language, and race. One of our goals is to make sure that the diverse voices currently reporting their research on policing, crime, law, security, and punishment are presented here. We are continuing our catch-up to develop article collections around different questions and themes. This post brings together articles on incarceration, rehabilitation, and recidivism from throughout 2019 and 2020, to identify the effectiveness of and limitations to rehabilitation programs within prisons, as well as alternatives to contemporary prisons in administering punishment and rehabilitation – including decarceration and rethinking offender reform and harm reduction.

Katharina Maier’s article, “Canada’s ‘Open Prisons’: Hybridisation and the Role of Halfway Houses in Penal Scholarship and Practice” was published in The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice’s December 2020 issue. Maier analyzes data collected from in-depth interviews with twenty-seven residents and fifteen employees of four halfway houses in a north-western Canadian city, in order to identify Canadian halfway houses as a form of Nordic open prisons. Open prisons, in contrast to contemporary walled prisons which process and hold as opposed to rehabilitate or help offenders, have been identified as exceptions to the punitive turn of Western contemporary carceral logic and penal systems. With halfway houses focusing on producing an atmosphere reflective of broader society, providing residents independence and agency, operating on a reward and punishment system, and prioritizing rehabilitation, Maier argues for their reconceptualization from post-prison institutions to open prisons. Throughout the article, she notes that halfway houses share many similarities to Nordic open prisons, and are viable prison alternatives which are capable of reducing recidivism within a controlled yet humane prison environment. The article identifies the harms created by incarceration in contemporary closed prisons, as well as the transformative role Canadian halfway houses could have not as post-prison institutions facilitating re-entry and seeking to repair harms created by imprisonment, but as open prisons and correction facilities themselves. As community-based alternatives to closed prisons, Maier argues that halfway houses could reduce Canada’s carceral footprint and address some of the issues facing existing correctional facilities.

The December 2020 issue of The Oriental Anthropologist included the article, “An Empirical Assessment of the Effectiveness of Offenders’ Rehabilitation Approach in South Africa: A Case-Study of the Westville Correctional Centre in KwaZulu-Natal,” by Patrick Bashizi Bashige Murhula and Shanta Balgobind Singh. Through semi-structured interviews and focus groups with thirty inmates and twenty correctional center officials, the authors argue that despite the South African Department of Correctional Services’ (DCS) mandate to provide rehabilitation services to offenders, the DCS failed in its implementation of the needs-based care programs. The needs-based care rehabilitation programs are designed to reduce recidivism by developing specific intervention and treatment plans and services based on an assessment of recidivism risks and needs, coupled with the South Africa rehabilitation principle which identifies individual inmate values, learning styles, and cognitive abilities. Despite potential benefits and recidivism reduction resulting from the program, challenges with implementation have hindered its effectiveness. The authors indicate that assessments were done with a “one-size-fits-all” approach instead of individually; there were a lack of prison resources and staffing challenges for social workers, psychologists, and educational instructors which limited programming; correctional officers and social workers were performing psychologists’ duties; and services were hindered by prison overcrowding (and a resulting environment non-conducive to rehabilitation).

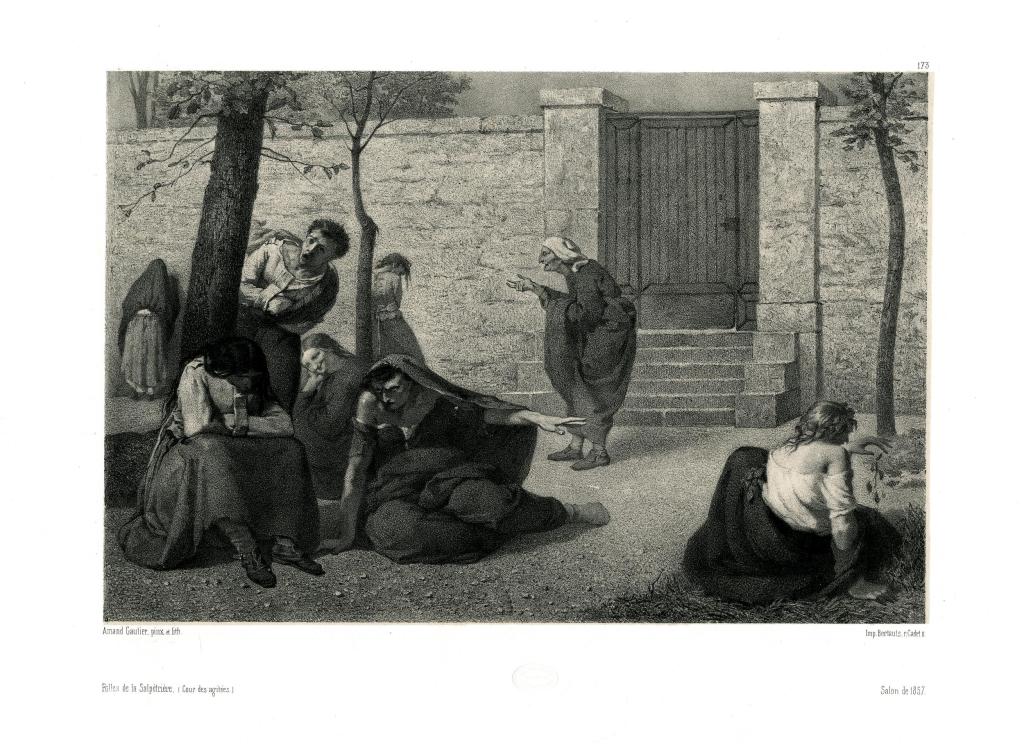

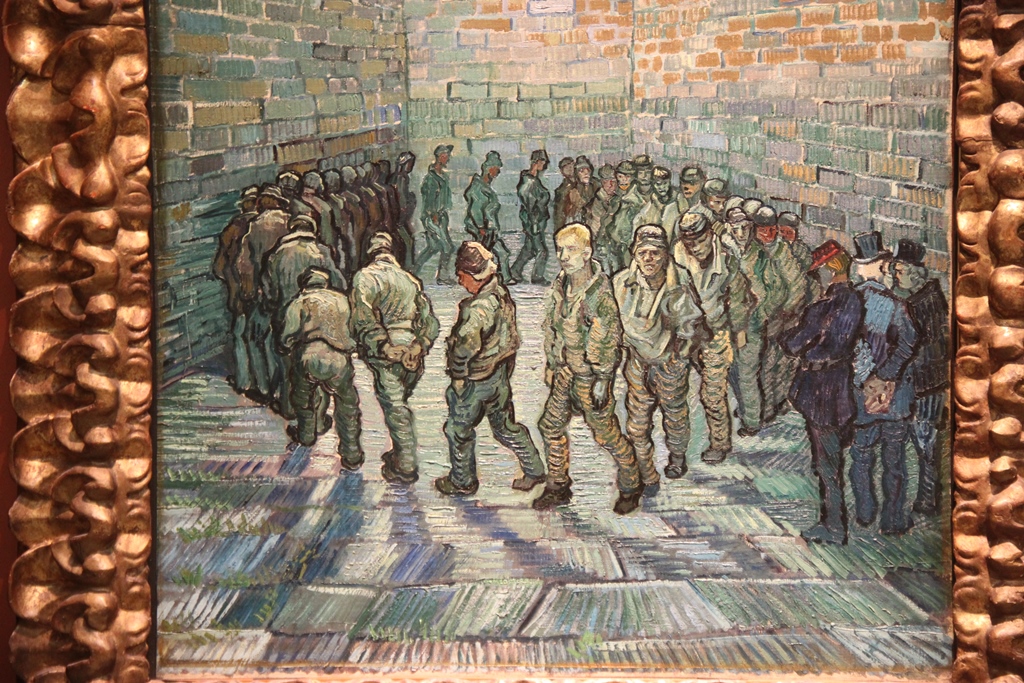

In the same issue of The Oriental Anthropologist, a similar article was published by Nozibusiso Nkosi and Vuyelwa Maweni, entitled “The Effects of Overcrowding on the Rehabilitation of Offenders: A Case Study of a Correctional Center, Durban (Westville), KwaZulu Natal.” The authors similarly discuss challenges posed by the correctional environment to rehabilitation, identifying overcrowding as having negative physical, social, and psychological impacts on offenders and reducing the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs. The article is based on ten semi-structured interviews with offenders, and five with correctional officers. While the correctional center provided the rehabilitation services as indicated in Murhula and Singh’s article, Nkosi and Maweni also find the same issues with program implementation. Nkosi and Maweni’s research identifies overcrowding as being the biggest challenge, as it creates conditions which inhibit rehabilitation efforts. Overcrowded conditions resulted in a lack of resources, inmate uncleanliness, insufficient medical care which decreased inmate health and increased deaths, inadequate sleeping arrangements, as well as less supervision and increased periods for inmates in cells. Inmates identified that conditions made them feel and behave like animals, increased incidences of violence and gang prevalence, and decreased their access to rehabilitation programs.

The California state’s attempts at dealing with the problem of overcrowding in detention centers through moderate decarceration, as identified by Victor Shammas, are incompatible with the system’s current belief that criminal rehabilitation requires punitive measures. Shammas’ article, “The Perils of Parole Hearings: California Lifers, Performative Disadvantage, and the Ideology of Insight,” appeared in the May 2019 issue of the Political and Legal Anthropology Review. Shammas utilizes fieldwork data collected from participant observation of twenty parole hearings in a California men’s prison, identifying that the state’s attempts at transforming the penal system to allow leniency in parole grants for inmates serving life sentences are futile amidst a hyperincarceration regime, with rehabilitation embedded and inseparable from retributive punitivity, and enmeshed in a culture of punishment. Shammas identifies parole hearings as oblivious hearings; hearings where parole boards were not actually listening, merely routinely completing a checklist of supposed insight and reform, which, if they result in parole grants, are likely be reversed by California’s governor regardless. Factors impacting board decisions include supposed ‘insight’ gained by inmates, performance and participation in rehabilitation programming, perceived self-sufficiency and self-improvement, introspection and transformation – all of which supposedly indicate likelihood of recidivism. In measuring inmates rehabilitation and recidivism likelihood by moral individual and responsibility measures, there remains a fundamental lack of listening and a heavy judgment of veridiction in parole hearings, both of which counteract supposed moderate decarceration measures.

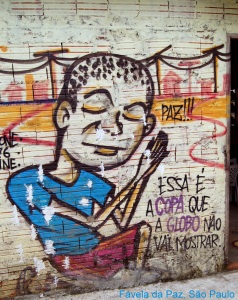

Suzanne Morrissey, Kris Nyrop, and Teresa Lee’s article, “Landscapes of Loss and Recovery: The Anthropology of Police-Community Relations and Harm Reduction,” was published in Human Organization’s Spring 2019 issue. The article uses fieldwork conducted in Seattle, Washington in 2012, with low-level drug offenders and commercial sex workers participating in the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program, as well as police officers and case managers. The LEAD program was instituted in Seattle as a collaboration between the United States Department of Corrections, Seattle Police Department, King County Crisis Diversion Facility, the Defender Association Racial Disparity Project, and ACLU of Washington State, in order to redirect low-level offenders to community-based services instead of prison, and reduce recidivism. With the goal of analyzing the effectiveness of LEAD’s harm reduction capabilities, the authors identify the effectiveness of the program in reducing recidivism through a combination of rehabilitation, mental health, personal livelihood and educational development, and legal advocacy services. LEAD participants were 60 percent less likely to be arrested within six-months than those who did not participate in the program, and identified an increase in their quality of life, that their needs were addressed, and relationships with law enforcement officers improved. The authors further note that the program reduced community stigma around offence, and bridged divides in opinion of community members, law enforcement officers, and offenders.

The June 2019 issue of Transcultural Psychiatry included Sandra Teresa Hyde’s article, “Beyond China’s drug century: Yunnan’s first therapeutic community and narratives of drug treatment and mental health care.” Hyde’s article is based on ethnographic research from Yunnan Province’s residential therapeutic community for drug users, Sunlight, which she mobilizes in her analysis of China’s contemporary response to recreational drug consumption and mental health crises amidst a so-called second industrial revolution. Through nine months of participant observation at the Sunlight facility over three years, alongside 80 informal and 30 formal interviews with residents and staff, Hyde argues that China’s rapid increase in drug use stems from rapid urbanization and globalization which threatened the economic situations and mental health of citizens. Despite its attempt to manage the drug use and declining mental health resulting from this industrial revolution, Sunlight, following a therapeutic community rehabilitation model, walks the same line of success and failure as past opium consumption projects in China did. As the first rehabilitation center of its kind in China, Sunlight continues to face challenges posed by the intersection of punitive and rehabilitative approaches, as well as the national and local political rhetoric of addiction and treatment.

As always, we welcome your feedback. If you have any suggestions for journals we should be keeping tabs on for this feature, or if you want to call our attention to a specific issue or article, send an email to anthropoliteia@gmail.com with the words “In the Journals” in the subject line.