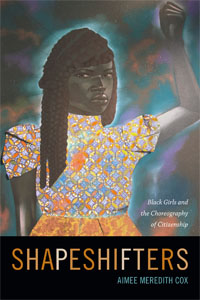

The editors of Anthropoliteia are happy to present the latest entry in on ongoing series The Anthropoliteia #BlackLivesMatterSyllabus Project, which will mobilize anthropological work as a pedagogical exercise addressing the confluence of race, policing and justice. You can see a growing bibliography of resources via our Mendeley feed. In this entry, Sameena Mulla discusses Aimee Meredith Cox’s Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship.

The editors of Anthropoliteia are happy to present the latest entry in on ongoing series The Anthropoliteia #BlackLivesMatterSyllabus Project, which will mobilize anthropological work as a pedagogical exercise addressing the confluence of race, policing and justice. You can see a growing bibliography of resources via our Mendeley feed. In this entry, Sameena Mulla discusses Aimee Meredith Cox’s Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship.

Kicking off the introductions of additions to the syllabus, I turn us to Aimee Meredith Cox’s Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship. My appreciation of this work and its power in the classroom in part stems from my own location, a private university in Milwaukee. The woes of rustbelt cities like Detroit resonate deeply with my largely midwestern students. While many of my students hail from predominantly white (often middle class) backgrounds, they are compelled by the youthful aspirations of the young women and girls Cox writes about in her book. Cox writes about Janice, her central interlocutor, Janice’s family, and fellow residents of the Fresh Start Homeless Shelter, revealing the masterful humor, wit, and clarity with which they navigate the challenges of black youth life in Detroit. Cox boldly preempts the Othering of her research participants, insisting to the reader that black girls are not a problem to be solved, and affording the girls space to “engage with, confront, challenge, invert, unsettle, and expose the material impact of systemic oppression” (7). Janice and her peers are bold, thoughtful, and creative. Some times they try, and fail. Other times, they try and succeed.

Cox’s ethnography theorizes like a jazz composition, with riffs, themes, and variations. She develops both “shapeshifting” and “choreography,” concepts that are important to think with in any context, but particularly poignant in this one (Detroit). The shapeshifting that Cox documents in her many-layered ethnography is one that resonates with puzzle working, “a method used to find solutions, master concentration, recall, recontextualize ideas, and map out plans” (28). As a life-long dancer, Cox develops and troubles the act of choreography, which she defines at one point as “shapeshifting made visible,” or “a map of movement or plan for how the body interacts with its environment,” while also suggesting, “that by the body’s placement in a space, the nature of the space changes” (29). Kevin and I recently exchanged some emails about the way choreography has entered into research on police work (see Lepecki 2013 as well as Luckett & Middlebrook 2016, below), but none of the work that I’ve read, as of yet, adopts choreography in quite the same sense as Cox. In some passages where she describes tensions between police and Detroit’s black residents, she demonstrates how White Detroit participated in embodied regimes of containment, creating racial boundaries.

While so much urban ethnography excludes women altogether, and black women in particular, Shapeshifter centers young black women, not simply as the subject of the book, but as authors of a world. Shapeshifters proceeds from a position in which black life matters, where young women are sharp eyed critics and citizen-subjects all too aware of where their rights and responsibilities are limited or truncated, and further aware (and willing) to adopt the innovative tactics they need to surmount or work around said limitations. Where my students might feel paralyzed (or claim to feel paralyzed), I can ask them, “What would Janice do?” And then, “How can you sustain and support Janice so that her tactics are more likely to succeed than fail?” Students may appreciate that they are navigating the same world that Janice and her friends are navigating, albeit from different places. It is a world in which policing asserts itself not simply through the efforts of formal police departments, but through various institutional, spatial and temporal regimes, and where young black girls navigate policing with boldness or subtlety, often while facing a limited set of choices.

Pingback: The Anthropoliteia #BlackLivesMatter Syllabus Project, Looking Back and Looking Ahead | Anthropoliteia

Pingback: The Anthropoliteia #BlackLivesMatter Syllabus, Week 26: Sameena Mulla on Missing Black Girls and Women | Anthropoliteia