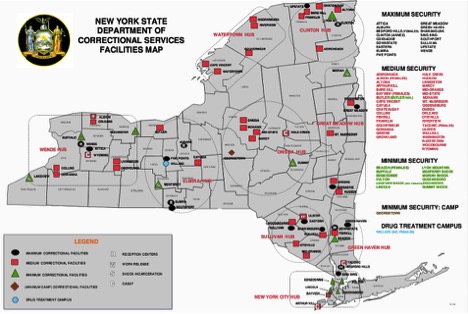

The New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (NY DOCCS) operates fifty-four prisons, which confine approximately 53,565 people. This captive population is ninety-six percent male; fifty percent black, twenty-four percent latino and twenty-four percent white. Though half of them were convicted for charges that occurred within New York City, most of them are confined in prisons located in distant, rural parts of New York State.[1]

I entered the visitor waiting room, a trailer that rests on the grounds of the prison. Though I arrived at 7:45am, a full 45 minutes before the start of visiting hours, the inside of the trailer was already full. I signed in at the rear of the space where two Correctional Officers (C.O.s) stood behind a tall wooden desk. I took one of the only available seats, which happened to be right next to them.

I entered the visitor waiting room, a trailer that rests on the grounds of the prison. Though I arrived at 7:45am, a full 45 minutes before the start of visiting hours, the inside of the trailer was already full. I signed in at the rear of the space where two Correctional Officers (C.O.s) stood behind a tall wooden desk. I took one of the only available seats, which happened to be right next to them.

The gender dynamic in the room was evident. Of the thirty-three visitors, I was one of only three adult males, and the only male that was not accompanied by a woman. The majority of these women had travelled from New York City, which meant that they left their homes at around 2:30am in order to make the more than 300-mile journey to arrive at the prison by 7:30am.

A large group of Black women of different ages carried on a light-hearted conversation about family and personal gossip. Every two or three minutes they burst into raucous laughter.

A Latina girl who looked to be about 10 years old, sat quietly next to her mother, who was speaking Spanish with another woman. The other woman had her bare feet resting on the floor next to a pair of gold stilettos with three-inch heels.

A young black girl at a different table was using an iPad while the older woman next to her sat quietly and stared out the window. She was dressed in white and wore a silver crucifix around her neck.

A group of white women, who arrived after all the chairs had been claimed, stood in an open area by the C.O. table, carrying on a hushed conversation.

These provisional fieldnotes locate and describe a fraction of the largely undervalued and under-theorized work that falls on the shoulders of women who struggle to support their incarcerated loved ones and maintain familial ties

Both of the C.O.s were white and both looked to be in their early forties. One was female, the other male. They wore bulky black combat boots and navy blue cargo pants, each with a ring of keys hanging from their belt loops. Their sky-blue collared shirts bore the crest of NY DOCCS on the shoulder. I noticed that their uniforms were faded and wrinkled. The male C.O.’s collar was unbuttoned, revealing a dingy white undershirt. Nothing about their appearance or affect inspired my confidence in their professionalism or expertise. Their conversation covered a range of topics including: gossip, drinking habits, hockey, the most desirable work shifts, divorce. . .

Across from the C.O. desk, visiting women took turns primping in front of two full-length mirrors. During the two hours I spent in that room, the mirrors were always occupied. One by one the women sat or stood in front of the mirrors and arranged their hair, clothes and make-up. When it was her turn, one young black woman plugged an electric pressing comb into the socket and straightened her hair. For the next 25 minutes, bellows of smoke and the scent of cooking hair filled the room. Other women waited patiently for their turns, showing no signs of aggravation or impatience. Above the mirror, signs in English and Spanish described the NY DOCCS clothing regulations, which prohibited low cut tops, cut-off shorts and bathing suits. While in the vising room, hugging, kissing and holding hands was allowed, but prolonged kissing or “necking” was not.

One woman entered the bathroom wearing sweatpants, a sweatshirt, and sneakers. She exited the bathroom wearing an intricately patterned blouse, form fitting jeans, and high heel shoes. She then fell in line to use the full-length mirror.

Just before 8:30am, the official start of facility visiting hours, one of the C.O.s yelled, “Packages!” When several of the women stood up and formed a line at the desk, each holding one or two large bags, I heard the male C.O. curse under his breath. One by one, the women unloaded the contents of their shopping bags and rolling suitcases, revealing cans of tuna and vegetables; bags of Doritos and pork rinds; cakes; cookies; nuts; packaged noodles and soups. As the women placed these items on the desk, the female C.O. recorded the last name and Department Identification Number of their loved one. She accounted for each item on a package form while the male C.O. repacked the items in a large paper bag, weighed each bag, then stored each bag behind the desk. Assuming that everything goes according to protocol, each package will be inspected and delivered to an imprisoned person.

The visiting women returned to their seats after being handed a package receipt. Many of them still had large bags of food with them. They brought these, I realized, to sustain them during the long trip home. They also had baggies filled with one-dollar bills or rolls of quarters. These were for the vending machines in the visiting room.

At about 8:45, the female C.O. matter-of-factly yelled, “One, two, three,” signaling that the first three people to sign in were now allowed to pass through the visiting entrance of the prison. When some, but not all of the women from the lively center table stood up for their visit, I realized that they had arrived separately and were visiting separate people. I began to wonder how they knew each other. Did they have histories that preceded the imprisonment of their loved ones or had they developed a sense of kinship and intimacy during the frequent bus trips that shuttle the families of incarcerated people back and forth across New York State? As the women left the trailer, other women from the table wished them a “good visit.”

Without the affective-political labor of these anonymous women, hundreds of thousand of incarcerated people would be crushed under the weight of the carceral empire

By 9:30 there were fifteen people still waiting to enter the prison and the conversation at the lively table shifted to more serious matters. The women had begun to discuss their interpretations of scripture and their faith in God’s divine plan. They also described the specifics of their loved ones convictions in ways that demonstrated their awareness of and fluency with New York criminal code and sentencing protocol. It would seem that many of them are actively working on getting their men out of prison.

These provisional fieldnotes locate and describe a fraction of the largely undervalued and under-theorized work that falls on the shoulders of women who struggle to support their incarcerated loved ones and maintain familial ties. These women write letters. They advocate for commutations, paroles, and retrials. They work extra hours to make up for lost income. They send food, money and photographs to their loved ones. They raise children and care for other family members. They dedicate significant time and effort to making themselves beautiful and attractive for their men. They form organizations to resist police violence and the prison industrial complex. They care for each other.

Without the affective-political labor of these anonymous women, hundreds of thousand of incarcerated people would be crushed under the weight of the carceral empire.

[1] New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. “Under Custody Report: Profile of Under Custody Population as of January 1, 2014.

Orisanmi Burton is a doctoral student in social anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Among his publications is article “Black Lives Matter: A Critique of Anthropology,” which is part of the journal Cultural Anthropology’s Fieldsites – Hot Spots series on “#BlackLivesMatter: Anti-Black Racism, Police Violence, and Resistance“. His twitter handle is @orisanmi Follow @orisanmi