As an anthropologist teaching in a Justice Studies Department, much of my time is spent with students who will pursue work in the justice field or in human services and community organizations. Accordingly, my students are often incredibly pragmatic about the material discussed in the classroom and how it might impact their understandings as it relates to future work. As such, I ask my students to consider course material relative to contemporary and interlocking social issues. It can be called intersectionality in the classroom; in social movements it is called solidarity.

I teach about BLM and racialized justice as an interdisciplinary scholar because there are many sources we can draw on for inspiration, whether we are reading Yarimar and Rosa’s piece[i] on “hashtag ethnography” or the Cultural Anthropology Hot Spot that Bianca Williams’ curated. I have taught most frequently with the William’s collection because it offers a wide-range of critical perspectives in the nine essays. Central to the importance of that collection, for myself, was Williams’ framing which included the following question/provocation: “how do we understand #BlackLivesMatter as an intersectional political and theoretical intervention, and how does this intervention help us to better grasp the connections between race, racism, and state-sanctioned violence?”[ii]

The answers to that question are concurrently pedagogical and political. I will start with the pedagogical and move to the political with the understanding they are interlinked as education should be transformative and driven by praxis, such that dialogue fuels action[iii].

The time and geographic distance to the US can make the names Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown and Eric Garner fade in the minds of some students in a smaller Canadian university—not all students, but some. Accordingly, I shift the content from year to year purposefully so that students do not imagine BLM as a historic issue but rather are confronted: with new findings associated to the cases; with communities and families that are left grieving but nevertheless continue to struggle for justice[iv]; with ongoing fights taking place to raise attention about racialized policing inside and outside the United States[v]; with the intersection of issues at stake when talking about racialized police violence so that Mike Brown’s death can map upon that of Neil Stonechild and Canada’s infamous Starlight Tours.[vi] I do this so students are not left to think that BLM was about isolated incidents of racialized violence but rather is part of broader discussions about systemic racism and structural violence.

I do so to illustrate that the punctuated moments of violence and resistance serve to highlight that we are talking about systems that must be challenged because they inherently breed violence. I do this so that students can draw connections between racialized practices across sectors and geographies. We can call this intersectionality and it is as students listen to Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout”[vii], while reading stories in the Cultural Anthropology collection and know that gender, race and class intersect. They do this, all the while connecting the issues of structural violence associated to BLM to the ongoing systemic racism associated to settler colonialism such that the death of Neil Stonechild relates to BLM just as the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s prisons is relational to the overpolicing of Black Men in the US. They do this and then we talk about the inverse: under-policing and who has access to what forms of the justice system.

When speaking about BLM, I explicitly position myself to students because it is important for my students to hear me articulate my position as a white woman relative to material that focuses on racialized police violence and justice practices. In positioning myself, I will discuss my own background working on racialized policing in the US or Canada, work that was done in solidarity. To teach is to then speak about what it means to be positioned, to have privileged access to justice, because I am not the subject of racialized policing practices. For me, this is what it means to be active and to teach from a space of solidarity.

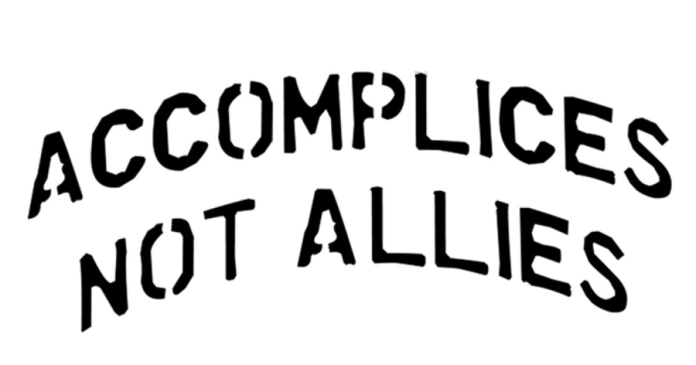

I used the language of solidarity purposefully because I am not an ally. Many are reconsidering the terms of engagement and what is at stake including Indigenous Action Media’s provocation that calls for accomplices not allies because as they point out, “ The self-proclaimed allies have no intention to abolish the entitlement that compelled them to impose their relationship upon those they claim to ally with.”[viii]

For me, this is what it means to be an engaged academic in 2017. There is necessity of that engagement, and to not be engaged demonstrates the privilege you occupy— and protect. I teach and act in solidarity. I teach and act as an accomplice. I say this because if we are not active in our community, then our complacency serves to prop up the very systems we teach and critique in the classroom. If we critique in class then we must be poised to move from discussion to praxis. For me this means working as an accomplice, not an ally, as someone who seeks to dismantle the systems of structural violence and systemic racism at the center of classroom discussions.

The risks of an ally who provides support or solidarity (usually on a temporary basis) in a fight are much different than that of an accomplice. When we fight back or forward, together, becoming complicit in a struggle towards liberation, we are accomplices[viii].

Work Citations

[i] Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. “# Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States.” American Ethnologist 42, no. 1 (2015): 4-17.

[ii] Willams, Bianca. “BlackLivesMatter: Anti-black racism, police violence, and resistance.” Cultural Anthropology. June 29, 2015.

[iii] Freire, Paulo. Cultural action for freedom. Harvard educational review, 1970.; Gramsci, Antonio, and Joseph A. Buttigieg. Prison notebooks. Vol. 2. Columbia University Press, 1992.

[iv] Whack, Errin Haines. “Trayvon Martin’s parents pen book on 5-year anniversary of teen’s death”. CBCNews, February 4, 2017.

[v] CBC News. “Black Lives Matter Toronto stalls Pride parade”. CBCNews Toronto, July 3, 2017.

[vi] Razack, Sherene. ““It Happened More Than Once”: Freezing Deaths in Saskatchewan.” Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 26, no. 1 (2014): 51-80.

[vii] Access soundcloud for recording: https://soundcloud.com/wondalandarts/hell-you-talmbout

[viii] Indigenous Action Media. “Accomplices not allies: Abolishing the ally industrial complex. Indigenousaction.org. http://www.indigenousaction.org/accomplices-not-allies-abolishing-the-ally-industrial-complex/ (Accessed April 19, 2017).

Michelle Stewart is an Associate Professor in the Department of Justice Studies where she teaches in the area of social justice and research methods and serves as the Director of the Community Research Unit. Her work explores contemporary policing practices in Canada with attention to programs and training that rely on collaborations between community, police and other agencies. This currently includes a project on how different communities of practice, including police, understand Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)..