This post is my first, personal, attempt at refiguring anthropological inquiry after the internet 2.0. I guess this is just a fancy way of saying that I’m beginning to try to come to terms with doing ethnography after the birth of social media. For context, my original fieldwork in France, way back between 2003-2005, coincided with Friendster, but that’s about it (it’s no coincidence that it was juring that time that I met my first “blogger”). I’ve long though about what it would mean to start up a new project in the age of blogging, microblogging, social media and whathaveyou. I’ve had various personal inspirations, and a few more or less inchoate collaborations (especially through the various iterations of the ARC Collaboratory, whose website seems to be down right now), but, at yet, no sustained engagement. So here goes.

View original post 1,255 more words

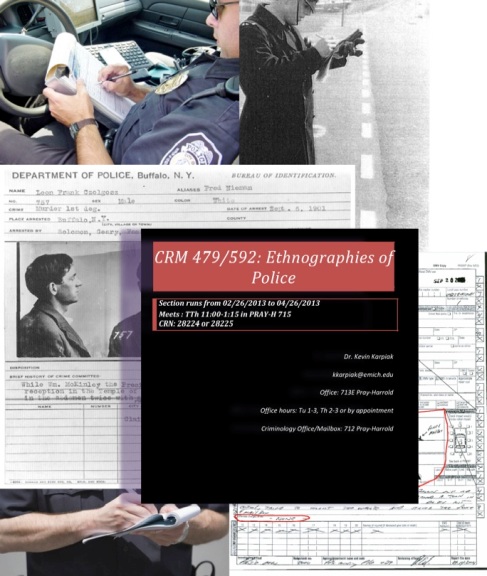

I’ve just uploaded a copy of the syllabus for a new class I’ll be teaching the second half of this semester, “Ethnographies of Police”. I’m pretty psyched about it. You can find a pdf version here, or go to the “Teaching” page of my blog and see it amongst the other syllabi uploaded there.

I’ve just uploaded a copy of the syllabus for a new class I’ll be teaching the second half of this semester, “Ethnographies of Police”. I’m pretty psyched about it. You can find a pdf version here, or go to the “Teaching” page of my blog and see it amongst the other syllabi uploaded there.

[Extended Deadline] CFP: Bureaucracy as Practical Ethics: attending to moments of ethical problematization through ethnography

Panel to be submitted for the American Ethnological Society & Association for Political and Legal Anthropology Spring Meeting Chicago, Illinois April 11-13, 2013

A significant strain of scholarship on the anthropology of ethics suggests that, since the Enlightenment, ethical thought in the West has been reduced to sheer will to power. A key point of evidence for this claim has been the reliance on bureaucratic forms of administration, which are highlighted as examples of alienating “anti-politics” machines of indifference. This panel hopes to challenge that broad understanding of the role of ethical thought within the contemporary world by using sensitive ethnographic accounts of bureaucratic praxis to explore how ethical challenges are confronted across a variety of contexts. The goal is to use these accounts in order to open up a conversation in which anthropologists might more adequately attend to moments of ethical problematization; moments that offer concrete opportunity for ethical refiguration and, therefore, ethical thought within contemporary political forms.

If you are interested in participating in the panel, please email a proposed paper title and abstract of no more than 250 words to Dr. Kevin Karpiak (kkarpiak@emich.edu) by Tuesday, January 22nd.

[Update: Since the deadline to submit panel proposals has been moved back, I’ve decided to extend this as well: paper abstracts should now be submitted by Wednesday, February 13th.]

Special Issue of Anthropology News features two articles on Police

Although there’s been quite a bit of rumbling over the AAA’s “open access” policies over the last several years, one positive development IMHO has been to move the association’s newsletter, Anthropology News, to an online and OA format.

Police propaganda billboard advertising goals for building a “Peaceful and Healthy Society.” This photograph was taken in Taiwan in the early 2000s. Photo courtesy Jeffrey T Martin

And now readers of this blog can benefit. The most recent issue features several articles on the Anthropology of Law in its “In Focus” section, including two articles on the anthropology of policing: one from Anthropoliteia’s own Jeff Martin, entitled “How the Law Matters to the Taiwanese Police” and another by Jennie Simpson, a recent PhD from American University, “Building the Anthropology of Policing” (the latter featuring a short–and unexpected cameo from yours truly).

Personally, I’m super-psyched that the anthropology of policing is beginning to carve out a space in the larger world of anthropology. Not only am I currently brainstorming how to incorporate these blog posts into my course on Policing in Society, but I’m secretly formulating a response to Jeff arguing that his use of my beloved Max Weber is all wrong!

In The News: Anthropologists, Criminologists (and some others) on the Newtown Shootings

I still haven’t found much of a voice or aptitude for addressing current events in a timeframe that seems relevant, so like the Trayvon Martin incident, I feel like this blog post is a bit “late to the game” and with less than I’d like to offer. This is of course made more difficult by the fact that research on gun violence has been blocked in the U.S. along multiple lines for some time.

Despite these impediments, there have been several serious attempts to gain an understanding of the role of guns and gun accessibility on mass shootings:

Continue reading

Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman and the Anthropology of Police

I’m sure I’m not the only one on this blog who’s been trying to think of a way to approach the whole Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman fiasco. Like a lot of scholarship, it’s just so hard to figure out what to add to the constant shit-storm of a media frenzy. But in my Police & Society class at EMU we have broached the topic, and the discussion has been both passionate and useful.

I thought I’d share the online discussion question I just prompted my students with. I’m curious to hear what readers of this blog might have to say. Here’s the prompt:

So our discussion seems to have gotten us to an interesting place: on the one hand, the question of what to do with George Zimmerman–did he have the right to be policing his neighborhood? did he have the right to carry and use a gun? did he have the right to suspect and pursue Trayvon?–brings us back to a question we’ve been asking repeatedly in the class… What should be the relationship between “police” and “society,” especially when we consider the use of force/power/gewalt? Should they be fully integral things, so that there’s no distinct institution of policing? Should there be an absolute distinction, so that only a small community can claim the right to police power? If the answer is somewhere in the middle, how would that work?

On the other hand, we’ve also been circulating around the question of freedom and security, norms and rights. Was George Zimmerman policing legitimately when we acted upon his suspicions, regardless of any evidence of law-breaking? Should the goal, the ends, of policing be the maintaince of community norms at the expense of individual liberty, or is a technocratic focus on law enforcement and civil rights the necessary priority of a democratic police force?

Anyone have any thoughts on how we can use some of the ideas and/or authors from this course to help us answer some of these questions?

In the spirit of continuing our discussion of the British “riots”, Jonathan Simon has an interesting post that I think echoes many of the things that came up in our own discussion. Here’s one particularly cogent nut he offers up in describing the importation of American criminal justice techniques to Britain over the past decade:

“….[C]hronic overuse of criminal justice as a ready made tool for addressing social insecurity under Neo-liberal economic assumptions has led to collapse of both deterrence and legitimacy.”

Now there’s a thesis. Thoughts?

Following up on the British “riots”: Jonathan Simon on GTC

Some thoughts on the London “riots”: Foucault’s genealogy of neoliberalism and “police as a public service”

I have to say I resisted writing this post. I have a visceral distaste for academic discursive hermeneutics performed from afar–this is partly why I’m an ethnographer, after all– and, that’s even more the case when trying to write au courant journalistically

However, despite having absolutely no ethnographic expertise among British police and only a concerned collaborator’s familiarity with the issues on the ground there, I’m going to just get over it–tempered still, hopefully, by a degree of humility and a recognition of our responsibility to ignorance. The reason I’ve made this decision is to emphasize an ethnographic fact that I think is important for this blog: so much of what makes police a salient issue in broader terms are in fact riots and, conversely, so many riots, uprisings and rebellions are in fact about police.

All that was a way of putting a large preliminary asterisk on certain observations I’ve made following the news coverage via my own personal extended network of interwebs (BBC, CNN, NPR, Jeff Martin’s twitter feed…). I’ve noticed a narrative dynamic emerging that I find a bit frustrating: on the one hand, news coverage presents the familiar “these are criminals/hoodlums without a politics,” with all its logical absurdities (is criminality innate and apolitical? If so, if these are innate tendencies and not the result of social conditions, how has London and then other cities in the UK suddenly–within the last several days– sprouted so many of this type? What would be the litmus test for whether determining this is a political act, by the way?).

On the other hand, often in an effort to show “the other side” or to emphasize some diversity of opinion on the events, news coverage includes another narrative which risks being equally tired and absurd, the “this is an expression of political-economic disenfranchisement” argument (with it’s equally non-falsifiable claims–what, again, are the criteria for deciding that this is political, and when where these events put to that criteria? what factors and/or data were considered? what would apolitical events look like? If at least one of these criteria should be statements of such from the protesters themselves, it does not seem to meet the definition…)

Even within stories framed in such a manner, however, I’ve noticed an interesting set of dissonances; some contradictions that, if properly attended to, don’t quite fit the dominant framing:

- Generational conflict. The “this is political” camp insists that the events are the result of the UK’s disinvestiture in social programs while experiencing wideing gaps in real wealth, but within that analysis there’s a type of inter-generational awkwardness, especially between what I think of as the Stuart Hall generation, associated with the Tottenham riots of the early 1980’s, and the present generation of protesters. What’s interesting is to watch the older leftists struggle with understanding and/or translating the events; I’m thinking of some of the interviews with the MP from Tottenham and others, such as Darcus Howe, who seem to be attempting to work out some space for understanding them within a framework of social dis-investiture in the absence of an actually articulated voice of such a grievance. The terms, or even the very language, seems to have moved somehow in the last 30 years.

- Policing is a social program. On the other hand, the “these are hoodlums” camp–set up as critics of the protesters (and thus anti-anti-dis-investiture)–emphasizes the affected business people and residents, often pointing to their calls for more police presence and in fact outrage at the lack of protection. The contradiction here, of course, is that policing is a social program financed through government. If anything, this is the voice criticizing dis-investiture. What to make of that?

I think a less contradictory framing is possible if we make use of Foucault’s geneaology of liberalism (which I’ve written a bit on before), itself formulated during a crisis-point in global capitalism, which identifies neoliberal efforts to “reduce government” as one strategy, within a longer history of liberal political thought, which attempts to find external principles of limitation on government. Part of why Foucault spends so much time on this is that it offers a prescient insight into so much of the nature of policing, security & surveillance today: namely that it springs from the same concern and theory of government. Although often misread, I think, Foucault’s point is that the policing techniques of surveillance (much used in Britain) which skeev many of us out are not efforts to achieve a tightly controlled police state, but the opposite: it’s a strategy of governance which, for many reasons, sees such totalitarian aspirations as ineffectual and unnatural. In this sense, security strategies of surveillance are attempts to provide a “policed” state (in the older sense of “happy, well -ordered and thriving”) with minimal police (in the sense of a specialized political organ claiming the monopoly of legitimate violence) interventon; police without policing.

In this sense, the policing strategies so heavily relied upon by Britain over the last several years are both part and parcel of a political rationality that also focused on finding more “economical” forms of government. The same rationality which leads to a dis-investiture of the social programs targeted by “austerity measures.” The two sides of the framing in the popular news-framing, then, are certainly not contradictory, nor is the one an effect of the other: they are two sides of the very same political rationality; one that more and more seems diseased. What will be the alternative? I’m not sure, but finding a useful answer, I think, depends on understanding the political logic in which we find ourselves.

New website for the Policing Studies Forum in Hong Kong

Just a note to let everyone know that our little seminar group in Hong Kong is slowly but surely growing a vibrant intellectual community around the interdisciplinary discussion of policing. We now have entered the 21st century with our own WEBSITE (yay!). The address is http://www.policingstudiesforum.com. Tell your friends and colleagues! And drop me a line if you want to get on the mailing list.