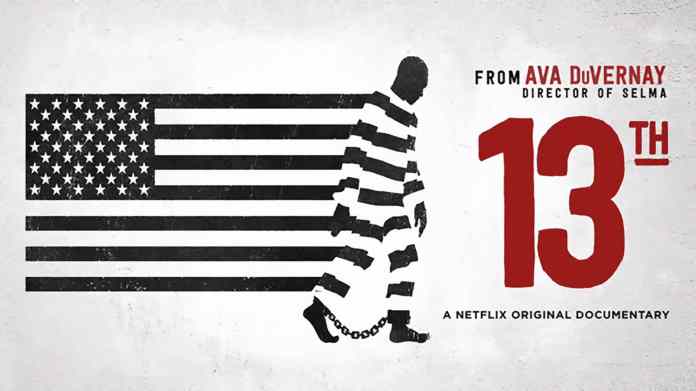

The editors of Anthropoliteia are happy to continue an ongoing series The Anthropoliteia #BlackLivesMatterSyllabus Project, which will mobilize anthropological work as a pedagogical exercise addressing the confluence of race, policing and justice. You can see a growing bibliography of resources via our Mendeley feed. In this entry, Maurice Magaña discusses seeing race and citizenship through Ava DuVernay’s documentary film, “13th.”

Within the first week of Ava Duvernay’s 13th release on Netflix in October of 2016, I began receiving emails from former students asking if I had seen the film yet. They were eager to discuss the connections between Duvernay’s film and content we had discussed in previous iterations of a course I developed called Youth, Culture, and Social Change. In that upper-level undergraduate course, we spent a good deal of the quarter discussing how youth of color have been pathologized and criminalized through academic research, public policy and the media, as well as the role of collective action in pushing back against these forces and crafting counter-narratives.

After watching the film, I understood why my former students reached out. Ava Duvernay managed to simultaneously- and in less than two hours- powerfully portray centuries of anti-Blackness, White supremacy and racial capitalism that have been rotting away at the core of our nation’s collective soul and institutions. She shows how these interrelated cancers continue to manifest though racialized police violence and the prison-industrial-complex, while also highlighting the voices and power of the formerly incarcerated, prison abolitionists and Black Lives Matter.

I also realized that I needed to show the documentary to the class I was teaching at the time- Introduction to Social Justice– which was a larger class of mostly freshman students, many of whom have family in law enforcement, border patrol, immigrant detention centers and other mutations within these overlapping industries of incarceration. Given the realities of the economy and racial politics of post-SB1070 Arizona, teaching about the connections between the inherent anti-Blackness of the prison-industrial-complex and the growing industry of criminalizing, detaining and deporting immigrants represents a very different challenge than my previous course. In what follows I highlight some of the pedagogical interventions that 13th makes, along with reflections on how I will teach this film in the hostile sociopolitical landscape of 2017.

Before getting into the historic and geographic specificity of the current carceral crisis with my students, I find it important to lay a foundation by unpacking a few key concepts: what it means to recognize race as a social construct used to create hierarchies of privilege and oppression; the power of labeling/“Othering”; what is human dignity; what is morality versus legality; and how citizenship is unevenly experienced. Once students have a firm grasp on these foundational concepts and distinctions we begin the heavy lifting of interrogating the prison-industrial-complex. While many folks in this country might have a hard time imagining that our prisons are filled with human beings worthy of dignity, most generally accept the laurels of the civil rights movement and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It is not uncommon to hear students- especially freshman- repeat the complaint that they wish Black Lives Matter activists, for example, were more respectful and law-abiding like Dr. King and the civil rights movement. 13th does a wonderful job of unsettling this dichotomy by highlighting the way that the CRM embraced and redefined notions of criminality. Seeing images of Dr. King and fellow activists being arrested destabilizes the sanitized image of the man and the movement that many students bring with them into the classroom. Moreover, this is a helpful moment for helping students understand the important distinction between morality and law. An important distinction to be sure- whether we are dissecting negative media portrayals of BLM or notions of “illegality” in relation to immigration. Here, I find the teachings of Rev. James Lawson especially useful in making these connections given his history and trajectory of nonviolent organizing and teaching.

13th foregrounds the central role that the War on Drugs has played in the current crisis of mass incarceration and offers a troubling glimpse into the evolution of the war from what Michelle Alexander describes in the film as “rhetorical” under Nixon to “a literal war by Ronald Reagan…that began to feel nearly genocidal in many poorer communities of color.” This section of the film resonates with previous lessons I cover in class regarding uneven policing practices vis-à-vis geographies of power and marginality. I show students the PBS film, Race the Power of an Illusion Episode 3: The House We Live In, which in addition to helping demonstrate the social construction of race as seen through changes in who gets to join the exclusive club of Whiteness vis-à-vis policies and attitudes around immigration and citizenship, also shows how these boundaries have been enforced and perpetuated through racist housing practices (i.e redlining, block busting, racial covenants). Before showing 13th, we also read and discuss “The Color of Justice” from The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander and “The Hyper-Criminalization of Black and Brown Male Youth in the Era of Mass Incarceration” by Victor Rios. These sources help students understand the huge disconnect between how Black and Brown communities experience and understand police, policing, and the whole criminal (in)justice system versus how White and more affluent communities understand and experience them, with an emphasis on the intersection between residential segregation, zero tolerance policing, and stereotypes around Black and Brown criminality.

To help drive this point home, I show video clips in class of media coverage of different groups of youth. Usually I show a New York Times video about a group of Baltimore dirt-bikers who, lacking access to recreational spaces for their passion, take their dirt-bike riding to the streets of their city. I also show a Vice News clip of a network of Mexico City party crews. I juxtapose these with videos of White hate crimes against Latino immigrants and fraternity violence. We pay special attention to the role of police and other authority figures in these cases, as well as the language used to describe the youth and their actions. The Black and Brown youth are overwhelmingly referred to as “gangs”, “thugs”, and “criminals”- even though their actions are at worst, traffic infractions. The latter, who commit murder and fire weapons into crowds, are referred to as “kids” and “students”. This exercise grounds our discussions around the roles that race, geography and class play in who is labeled a criminal deserving of feeling the full weight of the punitive state versus who is allowed to make “mistakes” and be treated as individuals.

Alexander’s piece “Color of Justice” introduces readers to some of the people whose lives have been devastated by the War on Drugs, like Erma Faye Stewart. In doing so, Alexander reminds readers of the racial dimensions of the Drug War- “Although the majority of illegal drug users and dealers nationwide are white, three-fourths of all people imprisoned for drug offenses have been black or Latino” (2). Actress, playwright and poet Liza Jesse Peterson drives this point home in the film- “The Prison Industrial Complex, the Industry, it is a beast. It eats Black and Latino people for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

The Rios piece sheds light on the power of labels to dehumanize and spread fear- specifically the labels of criminals, gang members and superpredators (the bad hombres of the Clinton era). Rios quotes John J. Dilulio and William Bennett, who served on the Reagan and Bush (W. and Sr.) administrations, coined the term superpredators and suggested draconian tough on crime solutions. Bennett is even quoted suggesting that if you wanted to reduce the crime rate in this country, “you could abort every black baby in this country, and your crime rate would go down… an impossible, ridiculous and morally reprehensible thing to do, but your crime rate would go down” (Rios 2006:51).

13th picks up where Rios leaves off by tying the rise of the law and order rhetoric that led to the creation of “superpredators” back to the GOP’s Southern Strategy and dog-whistle politics. DuVernay also interviews BLM and digital rights leader Malkia Cyril, who poignantly captures the impact of the media’s obsession with over-representing Black and Brown people as animals that deserve to be locked in cages, “Every media outlet in America thinks I’m less than human. I began to hear the word ‘super predator’ as if that was my name.” Victor Rios captures a similar perspective in his theorizing of the notion of “hyper-criminalization,” whereby youth of color are criminalized not “only” by the criminal justice system but also by their own communities (schools, community centers, neighbors) and families to the point where youth internalize their own criminalization.

Rios, Alexander and DuVernay all document the policy-side of this sinister war on Black and Brown communities by way of three strikes, mandatory minimums, truth in sentencing, and the 1994 Federal Crime Bill. Students are often shocked to learn that the bulk of these laws were enacted by the administration of Bill Clinton and in progressive states like California. 13th sheds light on the confluence of media and political forces that created a societal panic about Black and Brown criminality during the Reagan and Bush years, which set the stage for a Democratic “tough on crime” president. Terribly relevant in this discussion is footage included in the film from 1989 of the current U.S. president unironically calling for vengeance against five falsely accused Black and Latino teenagers in the infamous Central Park Jogger case. This case shows that 45’s obsession with stoking racial fears about Black and Latino men’s sexuality is sadly, not a new development. DuVernay does a masterful job tracing the disgraceful history of our nation’s hysteria and fear of Black men as rapists and threats to White womanhood and purity starting with an analysis of Birth of a Nation, all the way to examining the way that the Willie Horton case played out during the Dukakis-Bush election. 13th shows how Democrats learned to harness this fear of black criminality with Clinton’s election and his Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

13th also has a great segment on ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council), where DuVernay explores the connection between corporations, conservative legislators and devastating bills like the Stand Your Ground laws that Trayvon Martin’s murderer used to justify his killing and anti-immigrant bills like Arizona’s SB 1070. This is usually where I connect the rise of the prison-industrial-complex to the rise in the immigration-industrial-complex. We read the work of Tanya Golsh-Boza (sections from Immigration Nation and Deported) and watch the short clip by Cuéntame called Immigrants for Sale, which offers a crash course on ALEC, for profit immigrant prisons and the spread of anti-immigrant bills that seek to criminalize immigrants. By reading op-eds written by activists, like this one by Neidi Dominguez, and the student-publication Dreams Deported: Immigrant Youth and Families Resist Deportation students get an idea of the terror that immigrant communities are faced with via the immigration-industrial-complex, as well as the collective power demonstrated by undocumented youth, families and allies who pressured Obama to slow down his deportation machine. We also learn about BLM through the analysis of scholars like Robin D.G. Kelley, and perhaps more importantly by hearing the words of the founders themselves.

Although barely five weeks into the 45th presidency, it is clear that the momentum gained by activists towards scaling back the prison-industrial-complex and immigration-industrial-complex are under direct attack. It is crucial that students who are not down with millions of their fellow human-beings being swallowed up in cages and dehumanized in the name of corporate greed and fear-mongering politicians know that the work does not stop. That those students who are not okay with families being ripped apart in the name of law and order (i.e. what part of illegal don’t they understand anyway?) and nationalism know that those with dignity will never stop resisting. I believe that it is in this spirit that DuVernay ends 13th with powerful images of everyday Black folks living with dignity and love. I also believe that is the spirit in which poet Yosimar Reyes shared the following poem with us.

“Somedays you may wake up sad

somedays you may wake up frustrated

somedays you may wake up tired

somedays you may wonder if its worth it

somedays you may questioned your own growth

somedays you may think on how immense the world is

to be caged in this country

to be subjugated to all this abuse

somedays you just want to breath

And baby I am here

to remind you to sit in those moments

to sit in that whirlpool

but just know that there are people like me

picking up the load when you can’t

there are people like me pushing

so the weight of this country does not crush you

that there are people like you

who will fight when I can’t

we will take turns

pushing against these walls

I got your back and you got mine

and in the scheme of things does anything else matter

even if our fight is unfruitful

we will depart

with our dignity intact

we will depart knowing

that this country is losing

a prized possession

this country is losing

the gift of our resilience

We will watch them as they tear in to each other’s skins

and thank the heavens

we never turned beasts

like them”

– From A Poem so that the Weight of this Country Does Not Crush You by Yosimar Reyes

Maurice (Mauricio) Rafael Magaña is Assistant Professor of Mexican American Studies at the University of Arizona. He is a sociocultural anthropologist whose research focuses on the cultural politics of youth organizing, transnational migration, urban space, and social movements in Mexico and the United States. His research provides a transnational perspective on historic marginalization, racialization, youth political culture and the role of art in activism. Dr. Magaña is currently working on a book manuscript titled Cartographies of Resistance: Hip-Hop, Punk and the Production of Counter-Space. He is a member of the American Anthropological Association’s Working Group on Racialized Police Brutality and Extrajudicial Violence, a board member of the Association of Latina and Latino Anthropologists, and previously served on the board of the Society for the Anthropology of North America.