A study conducted through a collaboration of biostaticians and lawyers attracted attention this month, with the duo evaluating the overall success rate of the criminal justice system. Using death penalty cases as a “control group” of sorts, they argue against the claim that “99.973%” of US Court cases are processed accurately. They also found that ~36% of death row inmates are reassigned to life in prison if question about their guilt remains, fueling discussions of whether there is, in fact, an “acceptable” error rate.

A study conducted through a collaboration of biostaticians and lawyers attracted attention this month, with the duo evaluating the overall success rate of the criminal justice system. Using death penalty cases as a “control group” of sorts, they argue against the claim that “99.973%” of US Court cases are processed accurately. They also found that ~36% of death row inmates are reassigned to life in prison if question about their guilt remains, fueling discussions of whether there is, in fact, an “acceptable” error rate.

The ACLU called for a reconsideration of Border Patrol Officer discretionary power with respect to the use of deadly force. Does throwing a rock at an officer warrant a lethal response? John Burnett of NPR also tackled the question (somewhat unsuccessfully), while NBC Nightly News covered a DOJ report that also exposes a pattern of excessive force by officers in New Mexico.

Use of force gave way to topics in police technology, with attention being paid to the use of “shooting simulators” by some courts in Texas. The technology allows jurors to experience a simulation of a crime before it is heard in court. Praised by some for its ability to “put the juror in the shoes of the defendant or officer”, some insist it is a pro-law enforcement ploy to justify officer use of deadly force. Also in technology, a crowd-sourcing tool known as LEEDIR was used by the LAPD last month during investigations of a widespread riot. Officers praised its ability to quickly process digital evidence, while others point to its potential to subject innocent bystanders in public areas to police surveillance. Anthropoliteia author Orisanmi Burton also reflected on police technology in a post about Sky Watch stations in Brooklyn. Is this form of surveillance technology yet another chapter in the Domain Awareness initiative?

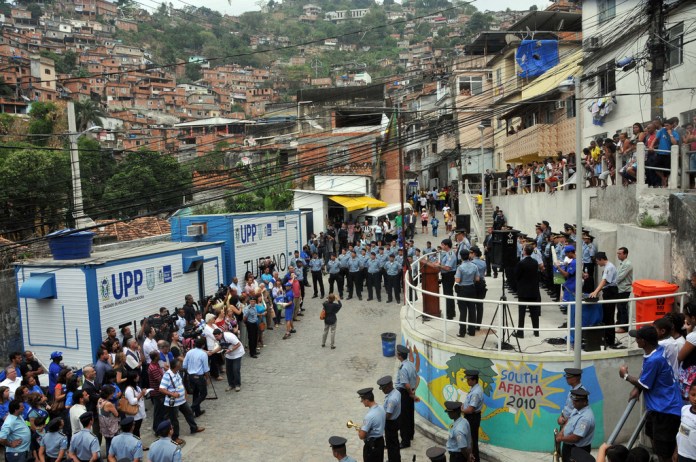

…just when you thought you knew everything Anthropoliteia has to offer, we throw a new feature at you! Guest author Stephanie Savell talks about the hidden side of police and security in Brazil. Fill in the gaps of World Cup media coverage with Savell’s holistic historical analysis.

Anthropoliteia was pleased to see former contributor Michael Bobick publish a piece through the Council for European Studies Reviews & Critical Commentary’s site. In it, he targets and addresses 3 questions about the separatist forces operating in Ukraine.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, about 1 in 4 adult in the US suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder. Perhaps stats like these are behind the growth of Crisis Intervention Teams. Read how one police department in Fairfield, CT invested (and benefits) from enrolling 20% of its officers in mental health response training. The role of mental health and policing lend to issues in homelessness, with Anthropology News featuring a thesis overview by Maegen Miller about the slow evolution of homelessness into a prosecutable crime.

Lastly, don’t miss 2014 Society of Cultural Anthropology conference materials that were presented on May 9th and 10th. Anthropoliteia’s own Kevin Karpiak and Michelle Stewart attended to present papers on the work of police. View the SCA 2014 agenda here.